If I Should Return To Society: A Report On The Substack Literary Scene In New York

A travelogue of readings and book launches

This piece will be a departure from the usual kind of thing I write, criticism and commentary where the singular ‘I’ is abolished. I will go back to that mode shortly. But for now, do indulge me as I discuss my trip to New York City, Ross Barkan’s book launch, and a reading at Matthew Gasda’s loft where he typically stages his plays, featuring a variety of known characters on Substack. I skip the more touristy events of my week to give you the thing you want to read about most: yourselves. I may have exaggerated some things, misquoted some people, or otherwise rewrote their lines because I liked my version of their dialogue better. So as you read this, remember: all writing is fiction.

I spent the week before my trip in New York defending my flight against fancy: I was going because I wanted some real pastrami, I was going because I wanted to take my girlfriend to Broadway, I was going just to satisfy a meager curiosity about the contemporary literary world in the one American city where it still exists. Surely all that would be enough, and yet, how do I justify going that far out of my way on a week’s notice? Why choose that week, of all weeks? Because Ross Barkan launches Glass Century, because he, Matthew Gasda, and John Pistelli would all be reading in the same rundown loft two nights later? I’ve had only the briefest interactions with any of those people on Substack. I did not know them. It would not matter to them if I were to come or not as I had already purchased their books. Moreover, I had no real careerist incentive for choosing that week instead of say, July or August, when I will be desperate to escape the Louisiana heat. I have no novel to sell, no article to pitch; The Metropolitan Review was already waiting for me to send in my review of Scott Spire’s Social Distancing, which this trip would only further delay. Why that week? What did I want out of New York that I refuse to acknowledge?

One of these safeguards was an avoidance of any media about old New York. I hadn’t been there since 2002, and I imagined it had undergone the same Blackrock Beige redesign of every other city in the 2010s. I tried to eliminate whatever Hollywood inspired conception of New York I still had. Still, the city was calling to me like a desperate itch. Maybe I was just missing really good pizza. For one reason or another, it felt like the time.

Tuesday, May 6th

Chelsea and I had hours to traverse the city before the Glass Century launch in the Lower East Side. We went through Times Square entranced by its spectacle, the Corinthian like screens adorning skyscrapers and turning advertisements into a modern wonder, theater Marquees and pub signs the size of IMAX screens. The cleanliness of it all. I was less put off by all this than I anticipated. So what if Times Square had turned into Disneyland and the strip joints and drug dealers were replaced with a giant M&M store? There’s a store now where you can create your own giant Reeses cup. We shared a frozen chocolate at Serendipity and my sympathy for the Fear City nostalgists evaporated.Maybe it isn’t real New York, but you couldn’t mistake it for any other place. The same could not be said of Wall Street which just looked like a larger version of Seattle’s Business District, or Williamsburg which looked like every “young” neighborhood of any city I’ve been to in the last fifteen years. Still, we were enamored with all the tall buildings that went on for miles. It was like everywhere I’ve ever been, but bigger and better

We arrived in the Lower East Side about thirty minutes before Ross was to be interviewed by Adelle Waldman and lingered outside a while before going in. The last reading we had gone to was Garth Risk Hallsberg’s The Second Coming at Octavia in New Orleans, where his million dollar advance and Apple Series adaptation of City On Fire brought in such a meager crowd that it appeared for a while that we would be the only people in the audience. The secondhand embarrassment she felt was almost enough to make her leave the bookstore and make me suffer it alone. More people did show up, but not until minutes before the event. So this time, we went in just a few minutes before it was meant to start.

We stepped through the P&T Knitwear entrance and it first appeared to be full, but not completely packed. On the left side of the store, Ross was standing in a grey blazer surrounded by men in corduroy jackets. When I got to the bar, I looked to the left and saw a gallery of raked seating two stories high, enfiladed top to bottom of young and middle aged alike, barely chatting, waiting eagerly for the reading. There must have been a hundred people up there. Chelsea took the last one. I would have to stand as if it were a basement punk show. No one knew what I looked like, and given the social anxiety accumulated from a monastic lifestyle of reading and writing and avoiding social life almost entirely that has gone on over three years now, I savored my temporary anonymity, walking past the suede shirts and denim jackets and tables of Blake Butler and Sheila Heti to the bar, not looking up, passing an unnoticing Ross surrounded yet by more guests, looking away still as if someone could have recognized me even if they saw me, and drinking my fourth espresso of the day. This anonymity was short-lived. I came out of the bathroom and saw Alex Muka, like a sore thumb with his hoodie and Yankees hat. Despite only ever meeting him on Zoom, where he could not see me because my laptop has no camera, he somehow recognized me with a single glance. Wayback Machine followed close by (we refused to call him “Daniel”), and the two of them, with only some assistance on my part, somehow made up the loudest corner in a room of over a hundred people.

“Deadass I ain’t ever seen this many people in a single room who have ever read a book,” Alex said, two pilsners in hand.

“I been to too many of these fucking things,” Wayback said. “Makes me wanna leave this city for good. It’s always some has-been interviewer with their tongue verbally down a wannabe writer’s throat and it’s for some shit like…” he picked a book at random. “This. What kind of title is this? A Little Life. Nothing with the word ‘Little’ in the title is shooting for the stars.”

“Guy on the cover looks like he's getting one biblical blowjob,” Alex said.

“I’m pretty sure that book is about a disabled guy who gets repeatedly molested,” I said.

“I could use a blowjob so good it makes me retarded,” Alex said.

“Can you say ‘retarded' here?” I checked my location on Google maps. “Are we in Dimes Square?”

“Dimes a few blocks down, but you’re good. The vibe’s shifted,” Wayback said. “Dimes Square people hate The Metropolitan Review by the way. They wouldn’t be caught dead here.”

The interview began and the crowd in the stands fell into a reverent silence while our half of the bookstore somehow got louder. I didn’t see many others I recognized, though I believe I saw the host of Book Club From Hell walking near the bar. A large redhead was strutting around telling everyone the Metropolitan Review owed him money. The bald guy next to him rolled his eyes whenever Waldman gushed over Ross. There was something invigorating about this atmosphere of competing reverence and envy. It was the first literary event I’d gone to where people didn’t seem to think their very presence constituted an act of charity. No disardent NPR utterances about “supporting bookstores” or even supporting Ross. People were there simply because it seemed like the place to be.

Chelsea was on her phone the whole time, taking notes of any overheard gossip I could use in this essay. Most of it I can’t.

“Chelsea does not give a fuck about any of this,” Alex said.

“Oh no, she’s not even on Substack,” I said.

“My wife doesn’t give a shit about this either,” Wayback said. “She said ‘Have fun with your nerd internet friends’ and stayed home.”

The reading portion was kept brief, and the interview went on for half an hour. Barkan discussed the autobiographical elements of the novel and his preference for Libra over Underworld. Alex grabbed more beers, and I was tempted to drink more, but with my 6:15 a.m. flight that morning, I was worried I might crash sooner than I wanted. I got in line for Ross to sign my book after it had time to die down, and the short bouncer, or the short clerk with the bouncer-like disposition perhaps, asked my name and wrote it on a bookmark. Ross wrote “To Adam, Thanks for Coming Out.”

Alex Muka said, “Bro, that’s Adam Pearson. Adam, speak up.”

“Oh, Adam Pearson?” Ross said. “Didn’t know it was you. Here, let me write you a better inscription.”

He invited us to the bar afterwards. I thought he said Emma Peel. He actually said something else. First I went to Katz’s, the New York pastrami haunting my dreams for months1, and after getting way more food than I could possibly eat, went to Emma Peel on Broom street. There, I talked to Alex and Wayback for another hour. Alex complained to Chelsea what a pain in the ass editor I was and that he was ready to kill me at one point. Chelsea understood, and said she would have supported him in that endeavor. Wayback bought me a couple gin and tonics and we talked about the fall of indie rock. I told him I’ve been wanting to read his book, but aside from being short on time, the death of rock was a sore subject for me.

“It hurts me too,” he said.

The jukebox was blasting The Offspring and Circle Jerks.

Eventually Alex had to leave. I gave him shit for it, it couldn’t have been later than 10 pm. But Chelsea was at his defense: “He’s a family man!”

We walked to Donnybrooks while Wayback regaled Chelsea with tales of cocaine, prostitutes, and a pre-gentrified Lower East Side. He then told me about all the pushback he had gotten from his agent by starting beefs with people like World’s Worst Boyfriend and Tao Lin, the latter which was DMing him.

“He said I can’t make fun of him because he has autism,” Wayback said.

“I thought his new book was about how he cured his autism?”

“Apparently he’s still got it.”

We got to Donnybrooks and Ross was half drunk, face red beneath the whiskywhipped curls. He stood upright and the swaggering blazer tails steadied as we all discussed Worst Boyfriend Ever, Wayback believing the guy was lying about what these women looked like, and my own theory that the entire project, aside from the van life, was a work of fiction. We agreed to get on Thursday before the reading in Brooklyn.

It was close to midnight when Wayback decided to head back to Brooklyn and the morning flight and four hours of unsleep were starting to take its toll. Matthew Gasda had invited me to his party at Funnybar. I pushed through the exhaustion and walked the four blocks back to the Lower East Side. We reached Funnybar and walked into a vortex of people and sound. The narrow hall reverberated every conversation into a jet hum and the bar that was barricaded by swarms of groups of three or four with conversations risible and subsumed into one loud unintelligible chorus. My sensibility as an urbanite (at heart, if not residence) was called into question then and I realized I had not the faintest idea how one socializes in this kind of environment. Chelsea, who had spent the first 28 years of her life in rural Mississippi, and the remainder thus far with me, after I had left my musician phase and entered a more introverted bookworm phase, had no interest in even attempting it. After about thirty seconds, she clawed her way out through the crowds and went back outside. She told me she would just wait outside there until I was done. I went back in and squeezed through the masses where there seemed to be a lounge area with tables. I saw Matthew on the far end, the low light of the table lamp glowing a sunset yellow against his face, his head ducked down as if in whispered stratagem of a morning sortie, and as I approached, he smiled as if recognizing an old friend, though we had not met and he too didn’t know what I looked like. “I’m just finishing up an interview right now,” he said. “But stick around, we’re gonna hang!”

I made my way back to the front door and stood outside with Chelsea for a few minutes. She didn’t mind being outside alone; we felt safer at night in Manhattan than we ever could in the South. Still, exhaustion was creeping on us both. I said I’d go back inside and visit with Gasda just for a bit. So I did. Matthew was hanging out at the bar now, recognizable in the dimly lit and multitudinous crevice of a hall even in his black turtleneck and charcoal blazer. We talked a little about an older book of his, The Blue Period, a fragmented modernist novella written in stream-of-consciousness with tortured but lyrical prose. My incessant insomnia of the previous week made it feel distressingly real. He seemed to have a knack for juggling multiple conversations at once while still making each person feel like the very center of his focus. This sort of charisma seemed surreal for a fiction writer—I myself am certainly incapable of it, as I proved a week later when Chelsea informed me I had been ignoring someone trying to talk to me the whole night unknowingly—surreal even for any non-writerly scene my memory serves as being witness to. And how was this man the same age as me? He appeared twenty five at best. It’s as if those years of thinking, reading, carrying a wide social net, walking from subway to subway, directing, debating, forming relationships, acting; all preserved a nearly vampiric level of vitality that those outside the metropoles can only observe on streaming channels. He stood in stark defiance of the life prescription to move to the suburbs and let your circle shrink as you age. After a few minutes, a hoard of attractive young women gathered around vying for a piece of Matthew’s attention, nearly pinning us against the bar. I felt like a cockblocker just hanging around, so I told him I’d see him Thursday at his reading and made my way back outside. I wondered if it was the city itself that incubated such charisma or if it just had a way of weeding out those who were not born with it. At the very least, there was a certain presence here that highlighted the somnolence of my usual interactions in day to day life; maybe these ‘scenes’ all do serve a purpose; illusory stakes and a short shock to the neurons. Or maybe this was just the Fancy speaking; if Gasda himself saw it this way, his new book wouldn’t be called The Sleepers.

On the way back to the subway a homeless man stood in the middle of the street shitting. He did not even squat, just stood normally as if waiting for the bus, while letting the pile beneath him grow.

Thursday, May 8th - Day of the Second Reading

I was half expecting Ross to cancel lunch. During his big week, there would have been plenty of more important people he could have spent his time with. Maybe it was from all the hustle-bro advice that invaded my tiktok and instagram feeds over the years, or the non-committal nature of the west coast whence I came, I assumed surely a man of his pedigree wouldn’t waste too much time among those unable to bring them up the next rung of the social ladder. This assumption proved inaccurate.

He invited me to a Polish restaurant in Greenpoint and treated me to a feast of pierogies, hunter’s stew, and white borscht, insisting on covering it all. It was the best sit down meal I had on the trip, as I would later fall victim to legacy tourist-baiting establishments like Patsy’s2. Maybe they were good back in the day, but not now). We didn’t drink, as it was still early in the day and we would be drinking later at the reading. He was shockingly easy to talk to—I don’t really have a reason for saying “shockingly” but for the fact I’ve never known a serious writer to be particularly charismatic; not that I’ve known that many serious writers—we found ourselves talking for several hours. In the middle of all this, the new pope got elected. An American. I brought up my mild disappointment with the lack of general conclaves I was expecting around Manhattan. “Like that street with Katz’s Deli and Russ and Daughters,” I said. “I expected it to be more Jewish.”

“You won’t find much of old New York in Manhattan,” Ross said. “There’s a pretty large Hasidic Jewish community in Brooklyn.”

“Is that different from a normal Jewish community?”

To think I was so worried about my cultured online persona collapsing once in person.

He asked me if I’d live in Louisiana my whole life.

“I’m from San Diego,” I said.

“But you have a southern accent.”

“I don’t have a southern accent.”

Grabbing the check, and not so much even raising an eyebrow, Ross said “Come on, let’s go see some Jews.”

We took the subway down to Oreb and got off at the hill of Sinai and the elusive taste of elsewhere greeted me at last. Walking through south Williamsburg in the somnolent heat the sable coats and sheitels moved like shadows sanctified passing us by without haste or notice. A group of young children rode past us on their bikes without a parent in sight, free and gleeful, payots shuffling in the wind. Though I was never so hung up on trad aesthetics before, I was smitten by the old world beauty not just of the 19th century garb and brownstone buildings but the easy air of safety and belonging in every resident’s gait. I felt like a smudge on an Isidor Kauffman painting. A virus that traveled not through space but time. I hoped I was as invisible as they all pretended, just some phantom of a distant Armageddon their faith was too sealed to know. I kept looking for a cherub with a flaming sword to come winking down the alley.

And here as if to break my trance Ross told me of their rituals and insularity. That even he, also a Jew, they would likely not speak to. I said of course they are insular, we come from a society of spiritual malaise and that rot is within us as well. Any society that contains no trace of it is not one we would find acceptable to live in, and any society that should remain without it, would need to keep people like us out3. He said that might be, that yes, there’s something special about Brooklyn hanging onto its old New York roots that allows these societies to survive, and of course, to be brought up within these communities entails pre-ordained meaning that those of the modern world need to find for themselves, even building from scratch. And yet, the Jewish people he most admires are not those in the shut off clans but those like his ancestors who opened up to the outside world and contributed to the American project: writing novels, forging industries, making lasting works of art. He said that in this new wilderness, this frontier that arises from the collapse of the old media empires, it is too exciting of a time to entertain such daydreams of old world isolation. Eden is lost but the American project lives on.

We cut across to the waterfront where glass towers seemed to sterilize the earthen heart of Brooklyn like the ridge of a biodome. Then we went back north and entered Capitol Hill, Seattle. Or was it Hillcrest, San Diego? Or was it Hawthorne District, Portland? Or was it Silver Lake, Los Angeles? Or was it Fremont, Seattle? Or was it Short North, Columbus? Or was it Downtown Olympia? Or was it LoDo, Denver? Or was it Oak Lawn, Dallas? It turned out to be North Williamsburg. I kicked the lower half of my shoe off to get the pebbles out but there were no pebbles, only blisters. We went through a bookstore and sat in the adjoined coffee shop.

“This whole week’s been surreal,” I said. “It’s like my online life has somehow merged with the real world.”

“Yeah, can’t believe we’re about to meet John Pistelli in the flesh,” Ross said. “It’s hard to think of him as a corporeal being with limbs. I just imagine him constantly floating over ethereal mists.”

“I think I’m too uncultured to hold a conversation with him. What could I say to John Pistelli that he hasn’t heard? Half of what I know about literature I learned from his podcast. He’d get bored talking to me after thirty seconds.”4

“I doubt that. John’s a really nice guy. Let’s see what he’s doing.”

At this point we had an hour before the reading. John didn’t answer at first, but later texted Ross saying he was in his hotel not too far from us. We picked up John at the Pod and made our way to the Brooklyn Centre for Theatre Research.

What to say about the real life John Pistelli? He came out dressed in all black and the sun instantly went down. He does walk on two legs, not a cloud of mist, and yet the lissome grace of his movement, the unassuming arms that even at a brisk northern saunter neither sway in their designated domain nor tighten against his ribs, the undulant head moving neither up nor down with the grey wisp of hair hanging unfettered yet unmoving against the lonely side temple, would have given anyone viewing him from the waist up the idea he was floating. He is one whose whole constitution seems neither resistant nor compelled but embodied by the greater mechanics of the universe; unassertive but unbending; not extraordinarily talkative nor shy but with such eloquence and exactitude of speech that as I expressed my unprompted regrets of having only read the first ninety pages of his book before meeting him he turned without missing a single beat and said “You read further than Val Stivers.”5

It was raining by the time we reached McCarren Park. A girl a few paces away asked her friend “Is it really raining?” and wiped the droplets off her phone to verify so on the weather app. We stood beside but not under a low somber oak and Ross and Pistelli discussed mysterious fact check requests from both the Times and The New Yorker. Pistelli was concerned that perhaps they were preparing for a hit piece on Major Arcana and Ross assured him The New Yorker was far too anodyne to write anything of the sort. Even if they attempted it, it would have no bite.

From the bushes on the other side of the iron bars, I saw someone with their phone pointed at us. They might have been scrolling tiktok, or they might have been procuring materials for blackmail. So these Metropolitan Review writers aren’t actually friends in real life, eh? Just found each other organically because they like each other’s writing? Well well well. Well well well.

The Loft Reading

I had finished Faust part one a couple weeks back and wondered how many Margaretes the city really had to offer. How many people go there for creative and intellectual pursuits just to be distracted by the veracity of experience instead? Moreso, I wondered what a moment beautiful enough for an author would look like. Is it the readings? Is that as close as an author can get to the spotlight? Even the bestsellers don’t experience any other form of attention in real time. Perhaps the only beauty to be found is in the composition itself, and a hope that one day when the muse calls there will only be minimal obligations in the way of their consummation. Having tried and failed various enterprises from music to stand-up comedy, I can see no other reason in abandoning the stage for the page, but the muse calls you there, no matter how much you protest, no matter how soon she ducks out for some other plans. Isn't it generous of a city that it can provide the literary writer just a parcel of that real life spectacle he has given up rights to in pursuit of his craft? Writers of serious literature only shine brightest after death, our existence here on earth as ghostly as our non-existence. This leaves us a dearth of big moments: seldom a big speech, no grand performance. A well attended loft reading is a bigger moment than most could hope for. I find it perfectly healthy to assume the peak of your relevance as a novelist happens only after death; if it fails to materialize, you won’t even know it.

We arrived at Matthew Gasda’s loft forty minutes before the start, and there was a sense of having arrived at someone's house party early. The entrance appeared like someone’s apartment, a sink and cabinets and across, a mini bar. Exposed pipes through the walls, shelves with fallen paperbacks of Stendhall and Baudellaire. This connected to the larger room with a couch and a microphone that constituted the stage facing about twenty to thirty foldable chairs. It’s the sort of place made for the audience to feel like part of some scene just by being there. I didn’t think units designed this way actually existed, I thought they were a Hollywood fabrication for movies like Rent. It brought another delightful if more subdued sense of elsewhere. After a while people started showing up, making bee lines to converse with Matt and Ross before the reading, then steadily tapering off from the highest ranked in the room to talk amongst themselves.

Per Chelsea’s request, I told Matt that she apologizes for not getting to meet him, she had to return home to not be late for her unpaid weekend on-call, and that place the other night was too loud for her.

“Ah. Where are you guys from?” Matt said.

“We live in Louisiana right now, but she’s originally from Mississippi, I’m from California.”

“But you have a southern accent…”

“I don’t have a southern accent..”

“You definitely have a southern accent,” Pistelli said.

Alex texted me that he was stuck in traffic, wanting to know if there were alcoholic beverages of any sort. There were. There was Johnnie Walker Rye which was good enough for me, among other stuff. He called me half an hour later and asked where the hell we were. He was on the roof.

“There’s like ten people hanging on mattresses listening to trippy music,” he said.

“How did you get on the roof without passing us?”

This mystery was never solved. He came downstairs and bought two Miller Lites and gave me one. I don’t care for Miller Lite, but I enjoyed his company enough to forget that fact. I had a similar experience reading his upcoming book, Hell Or Highwater, sort of raunchy millennial romp that used to dominate cinemas decades back, but with a more earnest romanticism, that I also assumed I wouldn’t enjoy. It’s not my normal cup of Miller Lite but I read it in three days. We talked about his book in the main loft, as more people arrived. Among them, a grey-bobbed woman with a Camille Paglia swagger who plans to release her novel on Substack as it was too subversive of certain MeToo narratives for the millennial agents she queried. If I recall it right, the plot had something to do with a woman going on a road trip with her stalker/grey-area-rapist. Maybe I have that wrong. It’s been a couple weeks now. There was another guy talking to us. I don’t remember who he was or what we talked about but he seemed very nice.

Matthew Gasda shushed the crowd, and when the guy with fake southern accent and the New Jersey guy finally shut up, he commenced with the reading. He read a bit from Sleepers, one of the many awkward unpleasant exchanges between Dan and Mariko. Alex whispered in my ear “My book is better than this, right?”

“Of course it is.”

“I mean at least I don’t use the word ‘bosom’ when describing a beautiful woman.”

“You wrote a novel for the everyman millennial, this book is clearly about a very specific kind of millennial.”

“Exactly,” he finished off his Miller-Lite. “My book is way better than this.”

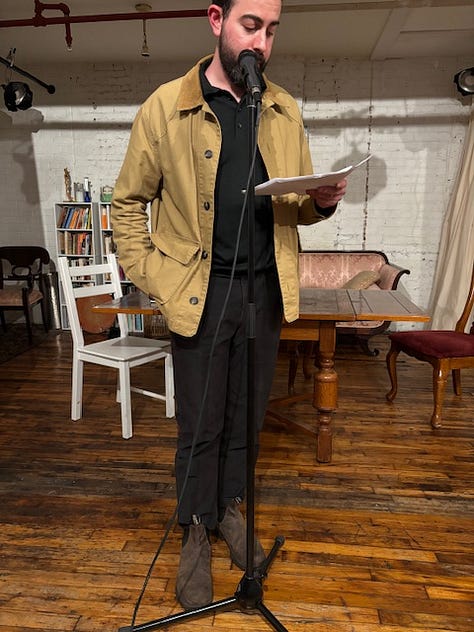

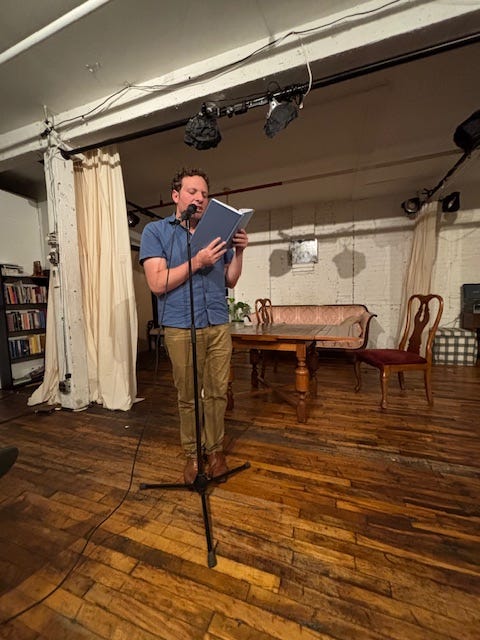

Ross got onstage and read the opening to Glass Century. After Ross—or maybe he went before, I don’t know—a different guy came on stage but he didn’t have a physical book so I don’t remember his name, or the book. I do remember enjoying what he read. John Pistelli came on last, and though I imagined him to have done less of these readings than the others, his was the most theatrical. Since I was seated in the front, I figured I should put my highly adroit photography skills to use.

The crowd was looser once the reading was done. Cocktails flowed and the whole room seemed to take on the type of open congeniality in stark opposition to how such New York literary circles are typically characterized. Secret Squirrel was there. We talked about opera a bit, and he discussed Alice Munro, how people unfairly viewed her as a kind of symbol for the MFA short story and her superiority to Cormac McCarthy. He was as verbose and erudite in person as he is in Substack notes. All of his thoughts just shot up like a geyser in a stream he couldn’t contain, from a well that could only ever be dug by a deep abiding passion.

By 10 pm, Alex had to go. A family man in New Jersey can only be in Brooklyn so late on a weeknight.

“You can’t leave now. You just got here. If you leave, I’ll be the dumbest person here,” I said.

“You’ll be fine. You're already the ugliest,” Alex said.

I bid my closest online friend farewell and returned to the party. My social battery was depleting, and the urge to read in bed grew. As I would have plenty of time for such a thing when I got back home in Louisiana, I searched for a conversation to join. One revolved around some French theorists I’d never heard of, another about the precarity of the novel’s identity in the 1970s. Derek Neal was mentioned, along with his populist positioning on the role of theory in The Republic of Letters. As were Sherman Alexie and Naomi Kanakia, both spoken of as world weary sages acquainted intimately with the underbelly of publishing and fell victim to the mob tactics of their original audience (I don’t know how much of this is true, I only read their newsletters). On the more regional side of things, there were tales of Honor Levy’s prodigious wealth and Christian Lorentzen's even more prodigious cocaine habit. Dimes Square parties at the mansion of Lauren Bush. In a city with this much fun to be had, how could anyone ever write a serious novel?

Nothing about this crowd reminded me of the fakers I’d read about in such scenes in various essays and novels. But I began to feel like one. Could any of these people see through me in a way I couldn’t see myself? They’ve all talked to hundreds of various versions of me. Dissected him. Ornamented him with dry and cunning prose. Hello Mr. Highbrow, your favorite author is Faulkner? You listen to Swans? You have an opinion on autofiction? Enjoyed that Tarkovsky film, did you? That’s all very interesting and very original. You’re going to the opera tomorrow? First time? Well don’t worry, I would never spoil for you the ending of Aida. Or Le Nozze di Figaro. Or anything else that everyone has already seen. I’m sure your literary takes on Substack are quite unique. I can’t wait to read them.

And Pistelli, sipping Italian liqueur, who even while talking to the attractive bartender seemed cognizant of every soul in the vicinity, with his third eye seemed to say Mr. Pearson, a dullard in person as with behind the screen? Who helped you with that one essay that got you that little bit of attention? That even enabled you to write for the Metropolitan Review in the first? If only I knew that giving you that little help would embolden you to come crash our scene like a little termite. You wrote a couple book reviews, congratulations. Also, why would I be thinking of any of this at all? You’re literally projecting your own neurosis onto me, not even attempting to capture my own voice, and adding “his third eye said” as if this weren’t a completely self contained dialogue in your head . I’m just trying to sell books here. But so long as you’re using me to personify your own superego, how sad is it that you don’t have that real psychic ability to penetrate the thoughts of others, that wide observant eye for any remotely realist novel? I’ll bet your entire body of work will be about your neurosis and nothing else, never reaching the true sublime that is a result of creating an entire world: try and look outward and you find only mirrors. This was supposed to be a scene report and you’re making this entire essay about you.

And Matthew Gasda’s eyes seemed to say: Wait, you’re still here? What do you want? Want to make a name for yourself by infiltrating some scene, like every other loser I’ve written plays about? Well you come a dime a dozen, go find a new square! You’re not even interesting enough for one of my Novalis posts. And internally I protested, No, truly, I don’t have an agenda. Bullshit. Everyone that comes here has an agenda. You not recognizing yours doesn’t make you genuine, it makes you dumb. You want a book deal? You want a hit piece? What do you want? But nothing. Did you come to New York hoping to make friends? Is that what you want? Jesus, that’s even sadder. Untrue! I have plenty of friends, I just saw one last year. Not happy with your social life down in Hicksville, Whereverthefuck? It’s actually growing quite a bit culturally , they just added a Starbucks next to the Best Buy. The local library even has a copy of The Tunnel and…

Ross brought me back to the reading home to help him settle a debate with Vanessa Ogle, who I imagine had some role in editing Glass Century, about Tad’s storyline. She wanted it cut entirely, and in my review from a few weeks before, I stated it should have been expanded. Ross seemed vindicated. He too wanted to expand the Tad storyline further. In her defense, the removal of the Tad plot would have resulted in a more symmetric product, with its social realism left fully intact. I’m starting to think the only kind of realism I enjoy is a ruptured realism, that with a chink in its plate, just a sliver of phantasma to upstart its Jamesian sleep before the dinner party commences and the sad professor’s eye wanders the hem of a new skirt.

I went outside and talked to John Pistelli about Faust part 1, which he recorded an episode on for Invisible College a few weeks prior, clarifying Faust’s pact with the devil. I wanted to ask him if the small bit of limelight of the evening was at least a little satisfying in some way, despite the fact that he spent $500 to ship a box of books to sell in a room of perhaps twenty people. Instead I asked him about Melville, whose Pierre I’d read back in February. In the chapter The Church of The Apostles, he stops the narrative entirely to shit on just about everyone working in the letters of his time.

“I get why Melville didn’t like Emerson or Kant. But Goethe is fantastic, what did he have against him?”

“The transcendentalists considered Goethe one of theirs,” John said (I’m paraphrasing here, he explained it far more eloquently than this). “Much of Melville’s later work is a product of envy. He was raging against what he saw as a clique that he couldn’t be part of.”

Back inside, a group of three guys were talking about diaspora fiction. A jovial and well dressed Indian man spoke of how people like Ocean Vuong were making it look cheap and tokenized. One of them had read my Orbital piece in the Metropolitan Review, and wanted my take on various topics. For one, he wanted to know what I, a southern man, thought of as a real deal southern writer and who I thought of as a faker.

Before Matthew left, he told us all we could all read our scene reports in the loft next time he has a reading, and takedown pieces especially. He was serious. I believed him. The Brooklyn Center for Theater Research and Dimes Square economy as a whole has always been generous to its critics, giving them a stage where they would have otherwise found obscurity. I promised him I’d write a grand takedown piece; one to match Crumbles.

“You mean Crumps?”

“Yeah, Crumps. What did I say?”

I don’t think I did a very good job. I simply don’t have anything negative to say about anyone I met (and I apologize too, to the readers who have read this far, hoping to find otherwise). Perhaps if I lived in New York, perhaps if my wide eyed illusionment wasn’t so fresh, if my acquaintance with the city was contingent on paying its rent and integrating into its networks, I’d known the real dynamics underlying these conversations about Hegel, or I knew any of these people intimately at all, this piece could have been snarkier. Even if I were to return in the foreseeable future, I don’t imagine the Brooklyn Center of Theater Research would care to hear any of this. Maybe next time I’ll do better.

By midnight, Ross herded everyone remaining to a nearby bar in Greenpoint. We passed a group of Russians diving through a dumpster. Someone had dropped a whole box of trinkets and vinyl records, the most boutique dumpster dive I ever witnessed. I figured even the hobos in Brooklyn must be gentrified. One, a woman that was anywhere between 19 and 40, with steady bangs dollike above marionette eyes happened to own a bookstore in the neighborhood. John gave her one of his books for free and she invited him to do a reading. She probably had a story about mother Russia more interesting than anything I’ve shared here, but my blisters were too outraged to stand around longer (even now, weeks later, their dead skin hangs on my middle toe) and so I continued onward towards the bar.

At this point it was after one am. The last time I’d been out that late was before the pandemic. I was surprised not to be falling over in sleep, maybe it was all the walking, or maybe it was something else, but I felt a renewed vitality. I almost wish I stayed later, got a little drunker, if only I didn’t have to navigate the trains back to Hells Kitchen. Ross bought me a few rounds, not letting me return the favor. I drank my gin and tonics, and he insisted I get back to work on my novel and keep a Substack output of one essay a month, at the very minimum. He said I would do well to move to New York, if I could afford it; that if I wasn’t planning to have children, there was no reason for me to be out in the suburbs.6

At 2 am I had to make my way back to Hell Kitchen, but 2 am? I haven’t stayed out that late in years. There is a vitality in that city I hadn’t experienced anywhere else and I’d been infected. I only thought a little about which interactions I’d made a fool of myself, but how wonderful those thoughts were. I haven’t cared about that kind of thing in years; that adolescent anxiety fades with the years but so do your memories, so do your wits. I hadn’t felt even a faint desire to impress anyone in years, but how much smarter would I be if I had? Fitter? More Charismatic? Better dressed? If I lived somewhere like New York, where it was acceptable for a man my age to wear something that’s not a ball cap or a golf shirt, I’d have quite the wardrobe. In the greater heartland of America the stakes have always felt low, a common refrain in the South of one’s fungus temperament is “he don’t need to impress no one cause he’s just real” and down here I’ve been one of those people, but not from any excess of realness. I think these lowered stakes are part of the allure when it comes to escaping the city, or at least a consolation. But the stakes get lower, you sleep through every conversation, become isolated, your arteries clog, you temper shortens, your paranoia grows, and after enough decades of that you’re making jokes you heard from the Bob and Tom Show back in 2002, scrolling youtube shorts about inner city violence, putting bumper stickers on the back of your truck, smashing your horn because the car in front of you stopped at a red light. This is what lies beyond the sunset you ride off to once you leave the city for the exurbs. But in the New York literary scene, the stakes are just right. No one can save you from your day job; no one on Substack, not even the New Yorker. There’s no loot to be had, and therefore no throats to cut. Literary prestige is dead, but a garden lives on, why not go read the writers you like and then go hang out with them? Why not go to Brooklyn and quote some dead philosopher you’ve never read? Quote enough of them, and you’ll have to read them just to save yourself from embarrassment, and you’ll be better for it. Pseudo intellectualism can only exist where intellectualism is valued in the first place; take it as a portent of better things to come, like a billboard for cracklins at the edge of Acadiana. Write that big ambitious novel: you still have an audience. The material benefits for doing so might no longer exist, but its metaphysical need has never been greater. Some famished but resolute soul might need it just to know it's still alive. Maybe that soul is New York’s.7

I’ll say it: Dingfelder’s in Seattle is better.

Someone could have warned me sooner to stay away from the legacy establishments. Never trust an Italian place that sells its sauce in grocery stores.

I know nothing of the Jewish faith, nor its mystic offshoots. My bias here is a protestant upbringing which has led me to rebuke evangelicism of any kind, be it faith, the carnivore diet, or the hype around the latest by Miranda July. Whether I dislike salesmen because they remind me of evangelicals or I dislike evangelicals because they remind me of salesmen is now beside the point: I believe in god more and more the longer I spend reading and thinking, but the only god I can currently envision in is not one with some urgent legible message he must insist his followers spread throughout, but an evasive god: one who hides in symbols, insists we know him in on his terms, indirect, communed with esoterically, so that anyone that should ever have known it would keep it like a secret: one need only look at civilization’s treatment of mother nature to know what it would do with the divine

I think I might have made a whole two minutes, actually.

Author of Compact’s takedown of Major Arcana, for those who forgot.

And here the Fancy rears its head again: that life here might be different from somewhere else, that these highly intelligent yet inclusive and affable members of the New York literati are the norm and not the exception, that that these rundown loft readings indicate a larger piece of bohemia to be subsumed in, in short, that a new city might realize in adulthood the ungained yearnings of youth. I predict I will consume and eject cities in an infinite crop rotation until I’m one of Beckett’s expelled, staring down death’s door, with no intact roots remaining to nurse me to the grave. And yet, as the roots grow more brittle, as my relationships across the country fade after having moved too many times, why not do it again? But yet, I don’t feel like my life would be much different if I did. If I should return to society, I’d only turn cold towards it once more. I’ve been to enough places now that I know that life in America does not vary by region. From plain to pine to bayou to beach the texture of life stays the burdensome same.

I was going to end this on a more climactic note, as my trip climatically ended with the final performance of Aida at the Met. That would take another 2000 words at least. Since you guys don’t write climaxes in your novels, I feel no obligation to write one in this novella sized post. I leave that memory with me, safe from the buzzsaw of narrative.

This is incredible. I’d pay for episodes of this.

I was highly amused. Glad you had a nice time!